1) What the fuck is going on?

Words, words, words . . . and more words. The next evolution of a rehearsal process that has been exhausting, exhilarating, fraught with discovery and failure. And now, as the ensemble bristles with the energy of the run, I can’t help thinking how wonderfully dangerous and visceral it is to perform when you’re surrounded by a group of actors, designers and directors who attack the work without fear and challenge you to rise with them.

2) What do you like about Shakespeare’s 400-year-old play Hamlet?

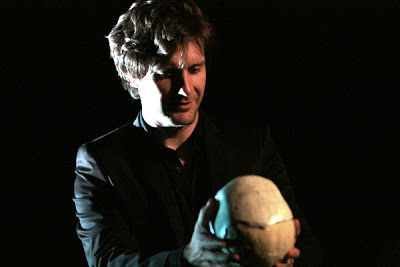

I think that the relationships are highly contemporary: a young man is distressed by the recent and sudden death of his father and then his mother marries his uncle; he has a girlfriend whose father and brother interfere with his relationship; he’s had to leave school to come back for his father’s funeral and now he’s stuck, out of his comfortable element, trying to reconcile how quickly people move on. I look at how fast everything moves around us and I connect strongly with where Hamlet begins – he wants time to grieve.

The play is an extraordinary unraveling of human experience, heightened to great effect by the supernatural elements, and Hamlet himself is a great deal of fun to play. He’s dense, complex, dangerous, funny, naïve – he’s everything all at once, which is, of course, unplayable and yet it opens infinite possibilities of playing to an actor willing to let the character in.

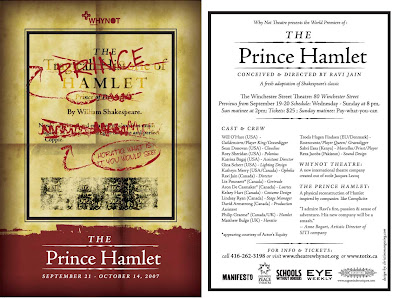

3) Why is the production called The Prince Hamlet, instead of its more traditional title, Hamlet?

3) Why is the production called The Prince Hamlet, instead of its more traditional title, Hamlet?

The actual title of Shakespeare’s play is The Historical Tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark, so in some ways calling the play The Prince Hamlet is no less arbitrary than reducing the title simply to Hamlet, but I like our title because it reminds us that this is a play about a person.

For me, the title Hamlet conjures over-studied ideas of the play as a literary entity rather than a performance text. A notion that is reinforced by dull English teachers and the egotism of so-called theatre practitioners who think that Shakespeare is sacrosanct and believe they provide the world a service by simply putting on the play and claiming universal relevancy.

Luckily, underneath all the crap is a good story.

4) What insights does the story offer about the nature of corruption and revenge?

I think of what Hamlet says to Gertrude in the closet scene when he tells her not to comfort herself by focusing on his behavior:

“Lay not a flattering unction to your soul, that not your trespass but my madness speaks. It will but skin and film the ulcerous place, whilst rank corruption, mining all within, infects unseen.”

Deception is constantly related to questions of honesty and authenticity throughout the story and I think in this moment Hamlet sums up the psychological cost of deceiving oneself.

He is obsessed with honesty and I think his revenge is slowed at first by his distrust of his father’s spirit (there is a much longer point here about what exactly Hamlet’s relationship was to his father – I choose to believe that his father was distant and indifferent and there is a clear hero-worship toward his father that, for me, belies a need to earn his father’s acceptance). Hamlet cannot, however, bring himself to act against Claudius until he has more proof and that leads to the play within the play. Revenge, at least for Hamlet, must be highly motivated and based on a certain conviction or “the pale cast of thought” weakens the resolution to act decisively.

5) Having played the character of Hamlet twice now, have you arrived at any conclusions about the character or the text that may not be obvious to the casual observer?

I haven’t actually performed the role twice, but I was in rehearsal for a production that was cancelled because of SARS. I feel incredibly fortunate to now have the opportunity to play Hamlet. The first time I rehearsed it I was very much stuck in my head with ideas about the play and who I thought Hamlet was and ultimately I’m glad to have been able to get a lot of my own bullshit out of my system in that process because it has made this rehearsal process much more free, challenging and exciting for me. This play comes with an unbelievable amount of baggage, but you can’t play ideas – the only things that matter are the story and the truth of the moment.

6) How do you feel about your time at the American Repertory Theatre/Moscow Art Theatre Institute at Harvard University?

Scarred. Rapturous. I learned the difference between art and banality and the emotional cost in pursuing this work. But I am but mad north-northwest . . . 7) What one thing would you change about theatre in Toronto if you could?

7) What one thing would you change about theatre in Toronto if you could?

I defer to Marquez: “But when the moment arrived he realized that anything might say would compromise his destiny.”

8) How important is it for theatre artists to be out there seeing lots of shows?

Theatre is discourse. If we don’t see other people’s work or remind ourselves of what it is to be part of an audience then we are operating in a self-serving vacuum and, unless you like the sound of your own voice, I see no point in acting in a vacuum.

10) Do you have any unifying theories that inform your approach to making theatre?

I constantly remind myself that I have to choose to allow myself to be bold, be brash, be brave, be physical, to remember that every utterance is a character’s act of survival, and that the stakes are always life or death. In the program notes for Peter Brook’s 1968 production of The Tempest at the Round House there were a series of fundamental questions the production set out to examine. The questions are: What is a theatre? What is a play? What is an actor? What is a spectator? What is the relationship between them all? What conditions serve this relationship best? Ultimately, I believe these are the only questions worth exploring.

Nice answer to # 9. I’m totally going to start ripping you off and responding with pictures…For instance when i want to say something is ridiculous, I will repost the photo of phil with a gynormous sombrero on his head….

I have the same sombrero. This is embarassing. Phil, if you plan on wearing it often we will need to sort out some sort of hat schedule.

Meredith