1) What the fuck is going on?

Oh, it’s just that sometimes we fail to see our interconnectedness and that causes us to treat one another badly. Don’t worry – we’ll get better at it.

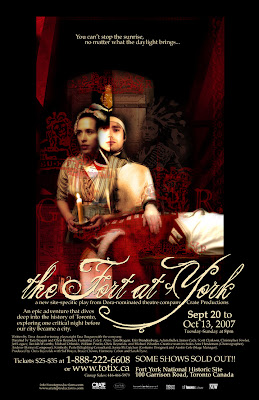

2) Does Crate Productions’ new site-specific play, The Fort at York, arrive at any conclusions about the importance of the 1813 Battle of York?

The prospect of creating the show excited me in the first place because I think there is a woeful lack of awareness as to our shared history in Toronto. Every person who lives here today has that one thing in common – the place we live – and yet we seldom take time to honour the people who kept the land before us. Learning some historical stuff, and putting that in human terms, increases our sense of community. The importance of the Battle of York is in the learning of it and the recognition that even if your ancestors were not directly involved, it is a part of your history if you live here now. We are accountable to the place we live and to each other – The Fort at York explores how and why that is a powerful thing. It makes our history relevant to our lives today, which makes us all a little more familiar to one another.

3) Seeing that mainstream historians often neglect First Nations histories in their cataloguing of North American “firsts”, how important was it for you to explore those elements of this story?

First thing outta my mouth when I met Chris Reynolds (producer and co-director) was that any play built around the events that shaped this city must deal with the absent ones – First Nations people and female people. So little is said about these cats in history and it makes me boil.

The show we arrived at represents both contingencies as they were – present, powerful, though not great in numbers. The presence of First Nations people at the Battle of York and the presence of women at the fort were significant, though undervalued in the day and today. Art can affect change, and voicing those who have been silenced is a part of that.

4) How have the site-specific elements of The Fort at York piece influenced your approach to preparing the script?

4) How have the site-specific elements of The Fort at York piece influenced your approach to preparing the script?

It set me up to be a rabid keyboard monkey. More than half the content you’ll experience in the show is new to this round, while some of it is reshaped from what existed in workshop last September. Once we got into it with a rabble of wildly talented folk, I found myself utterly bunged up without them and while off-site. I ended up having to type like a bastard during our three-week rehearsal process because I held off on writing until we got back into the space with our full crew. Thankfully, the actors have been brave and generate tons of tasty stuff. The site itself inspires, the actors run with it, and then I truck home and type until we have another go. Long process crammed into a short intense time frame. Joyous and mad.

5) If you could change just one thing about theatre in Toronto what would it be?

More serving story, less serving ego.

6) Do you have any unifying theories about theatre and its relationship to community?

Theatre is a communal experience. When we embrace that, and surrender to the reality that the audience is as much a part of the collaboration as the workers are, we get theatre that shines, moves, quakes. When we try to create a solid thing and then plop an audience into the room on opening, we most often get boring, stagnant dreck on stage. A theatrical experience must be a communal one among all the people in the room, and the presenters must welcome the change that comes from new energies nightly.

7) Are there any new stories being told?

Likely not, but we are telling them in new ways to people who constantly have new ways of hearing them. This makes them new to us – any new combination of people makes a story new.

8) What’s funny?

Something crass coming from someone who has no malice – my closest friends make me roar by saying the most horrible things. Barenaked honesty, such as my two-year old niece’s disgusted irritation when strangers want a hug from her. Having a loved one reflect your own idiocy back to yourself and realizing what a boob you’ve been, again, children are good for that.

Simplicity, summing up seemingly complicated things, such as the suggested tagline for this show as offered by actor James Cade: “The Fort at York . . . stupid war!” Anything that sticks out as incongruous can make me laugh on a good day.

9) What can contemporary Canadian theatre makers do to further inform themselves about our country’s First Nations performance traditions?

We MUST have a sense of shared space and bear in mind that the first people who lived here are relevant to our lives because we all live on land that was in their care for a long fucking time. Ironically, we put so little value in the spoken word when it hasn’t been documented. Oral tradition is a huge part of all First Nations, and yet the theatre community largely thinks Canadian theatre began with imitating European structure. It’s time to stop allowing the curriculum to shape our understanding.

10) As a writer, what are you better at now than you were five years ago?

I only starting writing stuff to share in late 2003. My first play was mostly written at the back of an aisle while working front of house for the Mirvishes: I feel I’ve improved in many areas, though my ability to stop mid-thought to help Americans to the can may have weakened since ’03. Certainly I’m better at . . . making choices faster, being more concise, cutting, guiding a group of people in a rehearsal hall to make sure the story is not misconstrued. Better at making use of a workshop, at figuring out a scene without having to get up and act it out. Better at letting grammar fuck off when it does not apply. Better at organizing my drafts into wee jolly folders.

The irony of Tara Beagan creating some relevant drama while on the Mirvishes dime is so thick we out to make a milkshake out of it.

Tara (or anyone else who wants to jump in),

What does this notion of recognizing “shared space” mean for our day-to-day lives? What should we do to recognize and foster that sense of shared space? Is private property ownership at odds with the greater good? How do we correct imbalances (with property ownership, for example) without discarding the good stuff that’s come from our current socio-economic model? How can we reconfigure our current learning systems so that they can redistribute information that’s locked away (and fading) in our oral traditions?

I can see shared space (and a sense of shared space) everywhere I look. But I can also see much space that is not shared. Private. Locked away behind fences of power.

How do we liberate our spaces?

Ian

“More serving story, less serving ego.”

Awesome. Tara, would it be okay with you if I put that on a T-shirt?

Ian – great questions, my mind is reeling, and I’m going to need some time to process all my thoughts on that. Vancouverites are notorious for segregating themselves in shared spaces (in bars, theatres, city commons, etc.), I’ve found that Torontonians seem to integrate with those around them with much more ease than we do. I have no idea why that is. I like the idea of using guerrilla theatre (I guess it’s ‘gorilla’ theatre in T.O.?) to unify an unsuspecting crowd, maybe even something with that very intent, hmmm…excuse me, I’ve got to make some notes…

Ian: First thing we can do is teach people to look at each other. Seriously. We seemingly spend half our lives trying to pretend that we don’t notice each other. We need to start doing that, without it being an exchange of “necessity”. I.E. I will look at you so that I may give you my order for that delicious hot dog you’re grilling up. (or sausage, if you’re into that sorta thing)

I’m not saying it’s easy. We’re all shy. But we can start by recognizing the space we share just walking down the street.

As an experiment. Today. As you’re walking down the street. Try to catch people’s eyes. And when you do. If you do. Give them a smile. See what happens. Bet they smile back. Or, if they don’t smile back, I bet they’ll at least be thinking “hey, that dude or dudette smiled at me … and that … makes me … feeeeel … unhhhhhhhh … good.”

And if they don’t do either of those, surely, the reaction will at least be much more interesting that simply passing them by without notice.

Hey Michael,

That’s an interesting project – and seems like a good starting (or continuing) point. Let’s see what happens.

Ian