The second in a series of short, photo-inspired essays on what it means – and how it feels – to be young, inexperienced and in love with the theatre.

Waiting – and waiting – for Godot

By Greg Kirk

The early stages of any self-initiated project are always fragile. Everyone has an idea that could easily – with difficulty – be transformed into something significant. However, the effort to actualize that idea usually produces no real indication of its significance.

When Simon Rice and I completed our production of Glengarry Glen Ross, our friends and family were all supportive, and the initial high of accomplishment made us take for granted that we were in the pioneering stages of something real and lasting. But as the days and weeks passed, life just eased back into its previous routines. I would get the occasional question about what show we would do for our sophomore effort, but it became easier and easier to just unthinkingly answer, “we’ll see.”

Fortunately, Simon went on a trip to England for a couple of months shortly after Glengarry (and, crucially, before life could drag him into the familiarity in which I was mired). With Simon gone and theatre far from my thoughts, I received a message from his mother that he’d been reading Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and planned to direct it as our next show. Whatever momentum I had lost, he still had it.

I think this is one of the key advantages of a partnership. I simply don’t believe that we human beings have the proper perspective to independently run our lives well. We need to disrupt the flow of our own familiar thoughts with those of others. This is a reminder that our way isn’t the only way. I believe this is what we call “inspiration.” Simon still had it, and I reacquired it from him.

The kids stay in the show

First, we simply didn’t yet know many people in the theatre community. We were all we had, and consequently had to wear many hats. Second, when you have yet to work with many other people on an artistic vision, it often feels as though the influence of others is a corrupting one; it takes time to recognize that others can respond to your vision, and can even enhance it. Third, at that stage, it was never clear how many opportunities would become available, so it made sense to take this chance to perform, direct, promote, and do absolutely everything for the show.

A quiet audience

What we failed to anticipate with this second production was that we were performing a considerably more opaque play for an audience predominately made up of friends and family, i.e., not really theatre people. Performing bombastic, profanity-laced monologues from Glengarry was easy, and a real crowd pleaser. At the end of the show, if you got charged up during your big scene, you knew it was good, and the audience clapped loudly.

Godot, on the other hand, can leave people a little pensive. The tepid applause we received opening night, from an audience all of whose names I knew, made me think we had failed somehow.

We went backstage and I said something like, “They sure didn’t love it.” I’ll never forget Simon’s response. He said: “Well, they probably didn’t understand it, so they’ll think that it’s art.” Looking back, I now think it was our best show.

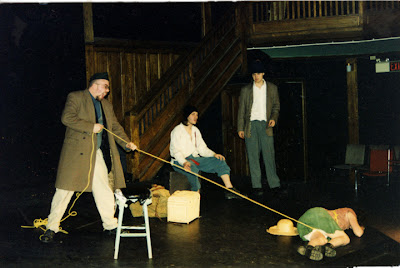

Cast and crew of Waiting for Godot from L to R

Cast and crew of Waiting for Godot from L to RAmy Withers as The Boy, James Spiers as Pozzo, Nick Drake the Stage Manager,

Simon Rice as Vladimir, Greg Kirk as Estragon, Sarah Wood as Lucky.

Our production played a little with gender. The role of Lucky, Pozzo’s (mostly) mute slave, is written into the text as a man. We thought it would add a provocative dimension to that relationship if it were a woman. This may or may not have been a little shallow, thematically, however, it produced an excellent performance from Wood, who went on to direct for Praxis Theatre.

We performed Godot at the Annex Theatre. The above photo was taken during rehearsal for a scene in which Vladimir and Estragon first encounter the bizarrely aristocratic Pozzo and his tethered partner, Lucky. During the actual performance, the stage was covered in leaves and a few hidden rocks. One night, when I jumped to the ground to eat Pozzo’s chicken bones, I unhappily discovered one of those rocks as it punctured the skin of my knee. I’m sure I yelped inexplicably, but it did provide a natural blood stain that was in continuity with the beginning of the second act, in which Estragon enters having been beaten the night before.

We performed Godot at the Annex Theatre. The above photo was taken during rehearsal for a scene in which Vladimir and Estragon first encounter the bizarrely aristocratic Pozzo and his tethered partner, Lucky. During the actual performance, the stage was covered in leaves and a few hidden rocks. One night, when I jumped to the ground to eat Pozzo’s chicken bones, I unhappily discovered one of those rocks as it punctured the skin of my knee. I’m sure I yelped inexplicably, but it did provide a natural blood stain that was in continuity with the beginning of the second act, in which Estragon enters having been beaten the night before.

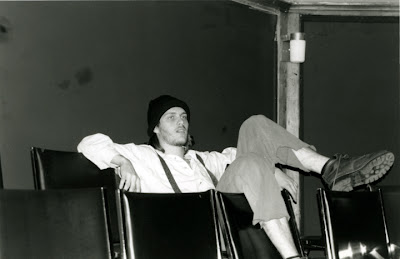

Me, in costume as Estragon watching a scene. You’ll notice I am wearing suspenders. We thought they looked better than the rope around the waist that Mr. Beckett’s script calls for. One of the unfortunate consequences of this decision made itself apparent at the end of the second act. The script calls for Estragon to take his rope belt off – causing his pants to fall down – and suggest they use it to hang themselves. They tug on it to test it, and it rips. We did the same with the suspenders, except they were elastic. Simon, as Vladimir, would always let go of them, causing us to fall down clownishly. Every night I expected the clasps to be sent careening towards my eyes. Every night I would be relieved as they merely welted me in the stomach or shoulder.

Me, in costume as Estragon watching a scene. You’ll notice I am wearing suspenders. We thought they looked better than the rope around the waist that Mr. Beckett’s script calls for. One of the unfortunate consequences of this decision made itself apparent at the end of the second act. The script calls for Estragon to take his rope belt off – causing his pants to fall down – and suggest they use it to hang themselves. They tug on it to test it, and it rips. We did the same with the suspenders, except they were elastic. Simon, as Vladimir, would always let go of them, causing us to fall down clownishly. Every night I expected the clasps to be sent careening towards my eyes. Every night I would be relieved as they merely welted me in the stomach or shoulder.