1) What the fuck is going on?

1) What the fuck is going on?

The wheels of time grind inexorably forward; our culture intensifies and multiplies, growing more complex as it fragments, while the corporatization of all things is the clear watchword of the age. We say what we say faster and make connections more quickly, but the time to make the leaps is the same – we’re running out of bandwidth, in the dark fiber infrastructure of our collective minds. We live in an age of empire in a time when even the idea of empire is becoming anachronistic, a time of vast injustice that differs from all the other ages of vast injustice only in the new skill with which we mechanize the injustice. We live in a time when it is easy to be faceless, almost required to be egoless against the great crush of people, but where surveillance is clearly growing to be a way of life. Also here is faith, love, honor, loyalty, friendship—the best elements human beings have to offer, still blossoming and blooming against the grain. It is a very interesting time.

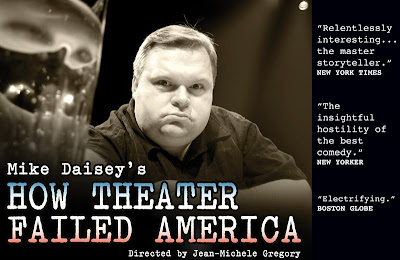

2) How does your upcoming production of How Theater Failed America in New York City differ from the indictment of American theatre (The Empty Spaces) you wrote for Seattle’s The Stranger newspaper?

First, the monologue isn’t written and the essay is, so this is the largest difference: one is an extemporaneous monologue, performed from an outline aloud only in front of audiences, which shifts from performance to performance and is deeply informed by that experience. The essay is an essay—words recorded once, in one order, 1,500 or so of them in an orderly row.

I stand by them both, but they’re very different animals—I am by career a monologuist, and in that form I have a finer control and larger canvas for the story of the failure of American theater to fulfill the social and cultural promises it made, and its own culpability in an increasing irrelevance. The essay takes a pass through that material that contains almost none of the personal, which is not the monologue – the theatrical piece weaves the personal and the political to one another, seeking something larger. Although they reinforce each other in the largest ways, they don’t have very much to do with one another in terms of plot or details – they’re basically separate works that are both created by the same person, and don’t share many moments, words, experiences or plot.

Some degree of their intention is similar though – both intend to provoke, in the best way I hope. I want to drive a wedge into the monolithic conversation about “our American theater”, which has often been stultifying—cracking open that shell so that fresh light can fall on all the old players, and opening up the discussion so that more people can hear the particulars are things that very much interest me in both pieces.

3) When you write about “how theater failed America”, are you suggesting that theater has failed America outright – and it’s a done deal – or are there glimmers of hope on the horizon?

3) When you write about “how theater failed America”, are you suggesting that theater has failed America outright – and it’s a done deal – or are there glimmers of hope on the horizon?

The monologue does attempt to make the case that the American theater has failed to fulfill its imperatives, particularly the regional theater movement, which I believe was a genuine attempt toward a provocative American theater rooted in excellent values. The tragic story of how that movement failed to fulfill its missions by losing its soul fascinates and compels me, and it’s the epic scale of what’s at stake that led to the title.

So yes, theater has failed America—but failure is to some degree relative, as is success, and we are still alive and drawing breath, so if we want change we’ll have to work toward it, as many of the people have before us. Some succeed, many fail, and most can never truly see where they live on that spectrum, but in terms of hope it is always alive, or there would be no monologue from me—if I did not truly believe in the transformative power of theater I would leave the form. I care so much that I’m driven to speak about what I see—and in the responses I see from people I can see the seeds of hope, just as I see it whenever I see heart-stopping, life-changing work.

So yes to both: theater has failed America outright, and yes, there is hope.

4) What attracts you to the monologue as a narrative form?

I’ve been a monologuist for 12 years now, performing in the extemporaneous idiom the entire time, and I’m drawn to the power that stories have to shape our lives. I work exclusively in nonfiction for the monologues, and there is an alchemy that exists in the telling of true stories from our lives, especially when they are told unscripted, mediated only by the outline, skill and experience so that there are as few barriers between the artist and audience as possible. I’m intensely interested in the livingness of this kind of theater, which is what has kept me riveted all these years—I believe it succeeds at creating a gestalt in the room between performer and audience that is irreducible, and which speaks to the enduring power of theater, as this is not possible in another art form, which makes me excited about its singularity.

I also appreciate how the lightweightedness and speed of the form allows me to survive in America as a working artist, in an environment that could otherwise preclude almost anyone else from making a living in the theater independently.

5) Do you ever worry that monologues are essentially one-way communication?

5) Do you ever worry that monologues are essentially one-way communication?

No, I never worry about that, because it’s a ridiculous question.

But I am very glad it’s been asked, because it comes up in interviews periodically, so I’d love to address it.

First, let’s address the straight-up bias: I only ever see this question posed to solo performers and monologuists. Yo-Yo Ma never gets asked if he’s concerned about the one-way-ed-ness of his music, and John Updike never gets asked the same about books, nor Joan Didion about her essays.

I suspect it’s born out of a prejudice, linked to ignorance, about the function of monologue. There’s a strain of Puritanism in America that supposes that we should not actually speak aloud about the events of our life – that it is louche and gauche and nasty to do so. After all, I’ve never actually read any playwrights being asked about how their plays are “essentially one-way communication” – that would be because people see more plays, and read more books, and listen to music, and thus have taken the time to realize that this is dumb. Under these terms all communication is one-way—each conversation is a series of one-way sentences, said back and forth to one another. The gestalt of course is larger – an essay is “one way”, but it exists in a society which will hopefully react to it, and that interplay is the actual conversation. I won’t do all the math—we all know how society functions.

I will say that it’s an especially galling assertion when you consider my actual form—I’m one of the very few extemporaneous performers in the American theater, and I believe I’m the only one with an established career playing major national theaters. My performances are completely predicated on the act of speaking with the audience—their presence informs and gives reason for the monologues to exist, and since they are unscripted their collective gaze is what fuels and helps guide the story. The idea that this kind of work could even be conceived as being “essentially one-way” is absolutely ridiculous.

6) How do you feel about the idea that American theatre panders to a cultural elite?

Well, it does pander—I’m not sure those it panders to are all that elite.

But I do understand the question. As for how I feel about that idea, I’d say that I agree that it happens a great deal, especially within the power infrastructure we think of as “the American Theater”—certain theaters, certain blocks of NYC, within a constrained world that gazes on itself—it definitely happens.

Specifically I don’t think of an “elite” though – I think more specifically of power groups that attract pandering, like the corporate donors and supporters whose influence grows continuously, or academia and MFA programs that encourage the training of young artists with absolute knowledge that they are no longer giving them living skills and sending them off to near-certain career death. Most times when this question is asked, we’re talking about audiences.

More than pandering it is narrowness, however, in terms of actual audiences—many theaters haven’t reached out beyond “traditional” markets, and when they have it’s a bitter failure. They pander because it is what they know. We shouldn’t hate them—they’re us, after all, our colleagues and our responsibility. If we want change, we’re going to have to bring it, and part of that will be learning to connect with others . . . and we’ll have to WANT to connect with others, which is a large unspoken part of the problem.

7) Looking back on your now-infamous April 2007 performance of Invincible Summer in Cambridge, Massachusetts – in which 87 audience members walked out of the theatre en-mass, with one man pouring water on your outline as he left – how much of an effect has that incident had on your subsequent work?

Very little. It was an unpleasant and disruptive experience, and the loss of my outline was total. I wrote on my site about the immediate aftermath, and managed to reach the man who destroyed my work to speak with him. While I wouldn’t call it a friendly conversation, it was civil and clarifying, which allowed me to put it to rest in my own mind.

8) What have you changed your mind about recently?

8) What have you changed your mind about recently?

For a long time I suspected that I would never write a play, because there is a large part of me welded to live performance that believes that the reliance on text in the theater is a large part of the theater’s weakness – dead words written by dead hands, propped up on stage. I still have many issues with this, but in the spirit of self-examination I participated in the Soho Rep Writer/Director Lab, and wrote my first play, The Moon is a Dead World, a Cold War fantasia of life and death set against the real-life brutal stories of the Soviet cosmonaut program. Living through the process has given me a greater respect for playwrights, and working in fiction has been absolutely fascinating and exhilarating.

9) How have your experiences with blogging and social media influenced your ideas about theatre?

My site has been a blog for seven or eight years, and has become totally interwoven into my work—it’s a mental clearinghouse of images and snippets I find on the web, a kind of open notebook that many people follow along with directly or through RSS feeds. Arguments, discussions, and lurking with the theatrical blogosphere has helped define elements of How Theater Failed America, and I’m indebted to other bloggers in many other fields for my other works. I’m also intensely interested in the cutting-edge of communication, and I’m working on a monologue about intellectual property rights that I hope will use all these tools in ways that will further the concerns of the work.

10) Why is theatre important?

Theater is important because it is the most human art form, because it is directly about the intricacies of the human heart, unfolding in an actual space in actual time between the humans on stage and the humans in the audience. It is storytelling writ large, without forgetting the core mechanic of storytelling – that the creation of narrative is the process of human consciousness, and seeing it play out, participating in that process as an audience member, is the highest calling possible in art.

Theater is not just important—I believe it is easily the most important art form that exists. In an age of increasing corporatization and identity-loss, it is a humanizing process that happens live in a space all around you, speaking directly with narrative and story to the concerns of a human being navigating the world. Theater is ourselves, the best and the worst of us, and as such we are charged with a terrible responsibility to work harder, deeper and more honestly to help ensure we’ve given it all we ever had.

Hey Mike,

I lived your interview. Especially your answer to #10. Just to inflate your ego, just last night, with no knowledge that this would be posted on my theatre company’s website, i had a long conversation with a co-worker about you last night. All the way up in Toronto.

It started with us talking about many of the parallels we saw in NYC and Toronto with the problems that you addressed in your Empty Spaces article, with an emphasis on our heros working 70 hour weeks at what works out to minimum age and how increased funding always seems to make it to administration instead of the artists themselves.

Then I learned that you were the same guy who had the infamous water pouring incident. The general conclusion was that if nothing else you were making an impact. Neither of us have seen your work and we’re talkin aboot ya in Canada. Thanks for your time and ideas.

“There’s a strain of Puritanism in America that supposes that we should not actually speak aloud about the events of our life…”

This puritanical strain also stretches north of the border!

Great interview!

Why is theatre important?

“it is a humanizing process that happens live in a space all around you, speaking directly with narrative and story to the concerns as a human being navigating the world.”

This is beautiful! Thank-you!

“. . . theater’s weakness – dead words written by dead hands, propped up on stage.”

Oh, God. Please don’t let this sentence fall into the hands of our opponents.

this is such an inspiring interview! thanks mike:) keep pushing the boundaries. i feel very challenged by your work.