1) What the fuck is going on?

1) What the fuck is going on?

Ask me in ten years. I will have it all figured out by then.

2) What is it about the story of the Diggers that inspires you to tell their story in public parks?

The way that the content of their story (a struggle for the right to own and occupy land, as a right of citizenship, not a privilege conferred by money), while so historically specific to England during the civil wars of the seventeenth century, lends itself to the circumstances of each place. My hope is that, even with all the distance of time and history, at least a few audience members in every place will be able to perform an act of translation that links this story to their own. The amazing thing about the experience has been the very broad range of response in each place. Naively, I wasn’t prepared for how extremely different each location would feel.

3) Why combine food, public parks and performance?

3) Why combine food, public parks and performance?

Audience! People love live performance, and they love parks, and they love food. These things share an ephemeral, lovely quality of pure, in-the-moment pleasure. Something only for the present time. Eating together brings the audience into contact with each other, which I think then heightens their response to a piece of theatre. Also, performing outdoors brings in a range of people who would never go to the theatre if they had to buy a ticket.

4) How do you feel about the potential dangers (to actors and crew, for example) of staging outdoor performances in at-risk neighbourhoods such as Jane and Finch?

4) How do you feel about the potential dangers (to actors and crew, for example) of staging outdoor performances in at-risk neighbourhoods such as Jane and Finch?

Frankly, I think there were none. The people who live in a state of danger are the residents, not us. If I ever felt uneasy, it was my own sense of comfort being disrupted, not the reality of the situation. It was amazing to see people trying to keep a very small yard tidy and full of geraniums while living next door to an obvious crack house. It certainly puts your own struggles in perspective to see people trying to live safely and cheerfully in very difficult circumstances. If anything, the consciousness of how protected we were – as outsiders – made me question slightly the usefulness of us being there, and whether such efforts to do something positive and interesting in a park need to come from within a community, not outside it, to be more than just theatrical gestures (pardon the pun).

5) Do you have any unifying theories about the relationship between community and theatre?

5) Do you have any unifying theories about the relationship between community and theatre?

Hhhmmm. Be playful, adaptable, and try not to be precious about the work (while at the same time never dumbing it down out of some idea that a mixed, non-theatrical audience can’t grasp subtle or difficult material). To try and create within a community, I think you need to let certain aspects of the work go, and realize that where you are will impinge on the process. And make that a positive thing – to welcome children and crazy people and bikers and dogs as interesting parts of the puzzle, rather than distractions (sometimes easier to preach than practice).

Not sure if that’s a unifying theory. The two things help and feed one another, and need lots of humour and silliness.

6) What does feminism mean to you?

6) What does feminism mean to you?

An ever-changing concept. Especially since I think, for women of my generation in this country (including myself), freedom is so taken for granted that feminism is often a word to be avoided, having associations of something doctrinaire, and maybe slightly prissy.

Feminism is an extremely loaded word – so much of it has been seriously flawed through concerning itself mainly with the rights of upper-income women to uncritically wield the same power as upper-income men, in the same limited sphere. I can’t get worked up about female stockbrokers making slightly less than male stockbrokers, since the fundamental assumption that certain kinds of work can carry a grossly inflated salary isn’t really questioned. However, it’s a good word to keep (and love).

In theatre, or art in general, I used to think it meant telling stories about women. I still think that, but now I also think it means women telling stories –about women, about men, about anything – with the same creative scope and freedom as men have always had. And perhaps telling lots of stories about men, and not censoring ourselves into feeling that we must tell stories only about women in order to be good feminists – god knows male novelists and playwrights have told stories from the female perspective without being accused of neutering themselves. Gender’s a fun thing. Play with it.

7) How do the various tenets of Stranger Theatre’s mandate manifest in the day-to-day operations of the company?

An unanswerable question. We really really really just make it up as we go along.

8) Are there any new stories being told?

No. Never. All stories have been told before. That said, all stories can be retold.

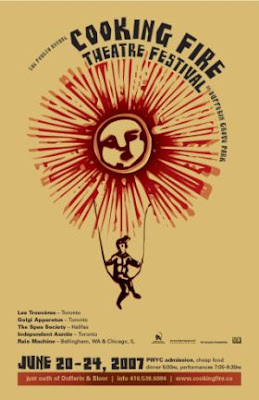

9) How has the Cooking Fire Theatre Festival changed since it started in 2004?

9) How has the Cooking Fire Theatre Festival changed since it started in 2004?

We are probably more organized (I hope). We have also been able to really develop artistic friendships with various companies as a result of the festival, and that gives us a base to work from. And we’ve figured out so many things about what will and will not work in a public park for the audience we have. Trial and error.

Of course, we now have it all sorted out and next year will be perfect in every way, with no flaws, snags or difficult personal dynamics.

10) Does your approach to directing theatre have much in common with your approach to writing poetry?

10) Does your approach to directing theatre have much in common with your approach to writing poetry?

I’ve thought about that a lot, since I love both very much, and I’ve come to the conclusion that they have nothing in common, except that both require precise and generous attention.

Theatre work requires so much presence. Writing needs distance, if anything. And is so private, a listening to oneself. As a director, you need to listen to others. I think of a director as someone who listens carefully, responds kindly and attentively, and tries to get out of the way of the actors, except insofar as they can shed light on what an actor needs. A performance is already there. The director doesn’t make it, ever. Just helps it to be. I think it’s also a question of time. Write a poem, then don’t read it for four months. Then you can judge it. Directing, you have to rise to the occasion because the only life of the work is happening right now, in front of you.

I saw the Diggers show at Lawrence Heights. What struck me most was how the edges of the performance didn’t start and stop with the raising of the curtain, so to speak. From the moment the Stranger Theatre van pulled up and started setting up the food stand, umbrella and stage, the park space came alive for me.

I don’t live in that neighbourhood – and I don’t want to make assumptions about how locals experienced the event – but from where I stood it was a wonderful and new social engagement with great food and performance.

And Kate’s totally right about food enabling conversation in the audience. I found myself engaged in several wonderful and unexpected conversations.

I spent my Sunday afternoon trying to replicate that delicious cabbage soup recipe.