1) What the fuck is going on?

What the fuck is going on? Everything and nothing. The Royal Shakespeare from Stratford is in town giving us The Seagull and King Lear in repertory at the Guthrie.

What the fuck does Trevor Nunn think he’s doing, casting Nina with a novice who plays Nina as a spastic high school twit in Acts One, Two and Three, and then compounds the problem by presenting her in Act Four as even more spastic and twittish? Is this condescending snobbishness on his part? Does he think we don’t know what the fuck this play is all about? Or what?

He compounds the problem by casting the wrong actor as Trigorin, giving him the wrong costumes and facial hair, and requiring him to be even more the juvenile hippy than Constantine. You can’t have two rabid teenagers in The Seagull competing for Nina’s affections, let alone Mother’s. What a travesty. Thank God one of our local critics took the Great Unassailable Nunn to task. Don’t encourage me. I could go on for hours . . .

I see Lear tonight. Sir Ian gave his usual performance as Sorin, more or less demanding our laughter with his full range of ticks and fruity asides. Has he been dieting on his reviews? Vide The New Yorker piece by John Lahr. His onetime lover gave up on Sir Ian, complaining it wasn’t much fun living with an animated theatre poster.

What the fuck else is going on? George Grizzard is dead. I told him a year ago he should give up smoking. Broadway now more than ever has abandoned itself to high schoolers, mostly female and quasi-female.

I first went to New York at Christmas time in 1942/3 as a kid of 20. In six days I saw Howard Lindsey and Dorothy Stickney in Life With Father, the Lunts in The Pirate, Katherine Cornell, Judith Anderson and Ruth Gordon in The Three Sisters, Tallulah Bankhead, Fredrick March, and a kid named Montgomery Clift in a brand new play Skin of Our Teeth, William Prince in Eve of St. Mark, Ezio Pinza in Boris Godanov at the old Metropolitan Opera . . . Then I went to war. And you ask me what the fuck is going on today?

2) What does feminism mean to you?

Wow. This is a really big question. Feminism for me is about bringing the stories of women to audiences. To create more female-driven stories and more female roles that are exciting and complex. To tell stories that haven’t been told because they were taboo or hushed in the past.

Feminism isn’t just about equality for me. It’s about the beautiful diversity that women add to this life. Women’s stories are men’s stories, children’s stories, stories of countries and cultures. These stories must be celebrated and debated. Personally, I feel that there are fewer roles for complex female characters in theatre, television, and film than there are for men. It’s getting better, but growth is slower than I wish for it to manifest.

3) What can contemporary Canadian theatre makers do to further inform themselves about our country’s First Nations performance traditions?

We MUST have a sense of shared space and bear in mind that the first people who lived here are relevant to our lives because we all live on land that was in their care for a long fucking time. Ironically, we put so little value in the spoken word when it hasn’t been documented. Oral tradition is a huge part of all First Nations, and yet the theatre community largely thinks Canadian theatre began with imitating European structure. It’s time to stop allowing the curriculum to shape our understanding.

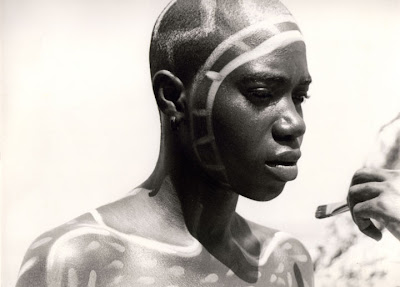

Philip Graeme

Philip GraemePhoto by Tony Hoffmann.

4) Do you have any unifying theories that inform your approach to making theatre?

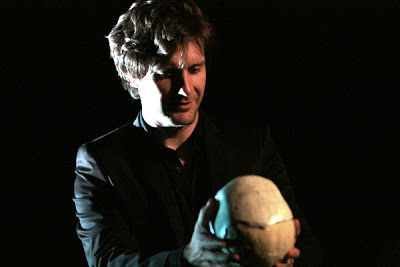

I constantly remind myself that I have to choose to allow myself to be bold, be brash, be brave, be physical, to remember that every utterance is a character’s act of survival, and that the stakes are always life or death. In the program notes for Peter Brook’s 1968 production of The Tempest at the Round House there were a series of fundamental questions the production set out to examine. The questions are: What is a theatre? What is a play? What is an actor? What is a spectator? What is the relationship between them all? What conditions serve this relationship best? Ultimately, I believe these are the only questions worth exploring.

5) What is “poetic theatre”?

Theatre that attempts to find clarity through ambiguity. Not verse theatre. Nor prose theatre or journalistic theatre. It is theatre that treats the text as a score, and treats the gap between actor and audience not as an obstacle to bypass, but as a medium through which multiple meanings can emerge. There’s a difference between shining a light directly into the audience’s eyes, and having it pass through a prism.

6) As a writer, what are you better at now than you were five years ago.

Everything, I hope.

I know I work harder than I did five years ago. I do know that.

The rest, I don’t know, I can only hope . . . life is a flawed work in progress.

I hope I’m smarter, more mature, more caring, more responsible and a better citizen than I was five years ago.

I hope I’m a more dependable friend to those I love and care about than I was five years ago.

If I can do those things and work hard, then the writing should take care of itself.

I can’t control whether or not someone digs my work or wants to produce it or even likes it, I have no control of that.

So I work hard as I can and try my best to speak to the truth.

That’s why writers and artists and musicians and poets exist, I believe.

To speak truth to power in a manner most excellent.

7) What qualities do you look for when committing to the development of an emerging artist?

For me personally, I look for someone who has something different to say and can articulate what it is they are striving towards. I look for someone who is at a point where interactions with other artists or with dramaturgy or direction are welcome and not struggled with. And finally I look for originality in ideas, in voice, and in presentation.

8) Do you feel that the CAEA is currently living up to the spirit of its mandate?

For Council, that is the most important question of all.

Our mandate comes from the owners of Equity: its members. The mandate is not a static thing. Theatre changes, the world changes, and members’ needs change. The only way for us to keep on top of a living mandate is to regularly consult with the members.

To that end, we have just concluded a major survey of our membership. This will tell us what our mandate is going forward, how we are living up to it so far, and what we need to do to improve.

Although complete results are not in yet, what we have seen so far suggests that we are living up to our mandate in the areas that the members commonly regard as the most important. Beyond that, they would like us to improve in providing some of the “soft” benefits of membership, such as advocacy, advice, and various resources. Please be aware that I have just condensed 1,500 pages of results into two sentences. It is a much, much more detailed picture than that.

9) What does post-modernism mean to you?

Revealing the sometimes-hidden content in form and vice-versa.

10) How well are Black Canadians being served by and represented in contemporary Canadian theatre?

what is contemporary theatre? If you mean the mainly publicly funded, mainly media supported, medium-to-large theatre houses, clearly there are not many black people (meaning womben and men, however womben especially), or first nations people or many other people of colour or differently abled people). the reason for this is clear – longstanding legacies of colonialism and imperialism (racism, sexism, classism, etc) dating back to the very stealing of canada from first nations people.

that being said, my own understanding of contemporary theatre is theatre that is being created now, today, which is happening all over; which does get some media support. If this is what you mean then I definitely feel that black canadians are both being served and represented because we are creating our own theatre and have been since we have been in canada, both as enslaved afrikans brought over on ships and as new immigrants choosing to come here voluntarily.

I am becoming less pre-occupied with being served by the former definition of ‘contemporary canadian theatre’ and more concerned with creating it. I feel that that is one of the solutions I can offer. therefore I feel that indeed in creating the stories that I am telling, I am serving canadians and am representing myself.

a major part of the reality is that as human beings we seldom relinquish power or share it simply because that is the ‘right’ thing to do. usually something has to be at stake or a gain on the part of the power-holder has to be identified. for me this has always meant removing myself from scenarios that may compromise my ability to have power over myself. Self-determination is essential in identity, self-esteem and community building.

I feel that as people in general we are responsible for telling our own stories and creating the means by which to tell them. there are some serious concerns around funding and access, however like I said these will not disappear over night so what do we do in the mean time? wait? no. we create. we live. we dialogue. we change ourselves and our families and our lovers and our friends. and we do not give up our power over self by waiting for power holders to share power. we simply create another reality in which we can find self-empowerment and positive self-reflection and collective dialoguing about change; tell our own stories. I am also less concerned about having these dialogues in the vacuum of acting/writing for theatre and more concerned with having them across broad socio-political-economic circles because these systems are old and entrenched so changing them needs a complex inter-connected circular approach.