1) What the fuck is going on?

1) What the fuck is going on?

What the fuck is going on? Everything and nothing. The Royal Shakespeare from Stratford is in town giving us The Seagull and King Lear in repertory at the Guthrie.

What the fuck does Trevor Nunn think he’s doing, casting Nina with a novice who plays Nina as a spastic high school twit in Acts One, Two and Three, and then compounds the problem by presenting her in Act Four as even more spastic and twittish? Is this condescending snobbishness on his part? Does he think we don’t know what the fuck this play is all about? Or what?

He compounds the problem by casting the wrong actor as Trigorin, giving him the wrong costumes and facial hair, and requiring him to be even more the juvenile hippy than Constantine. You can’t have two rabid teenagers in The Seagull competing for Nina’s affections, let alone Mother’s. What a travesty. Thank God one of our local critics took the Great Unassailable Nunn to task. Don’t encourage me. I could go on for hours . . .

I see Lear tonight. Sir Ian gave his usual performance as Sorin, more or less demanding our laughter with his full range of ticks and fruity asides. Has he been dieting on his reviews? Vide The New Yorker piece by John Lahr. His onetime lover gave up on Sir Ian, complaining it wasn’t much fun living with an animated theatre poster.

What the fuck else is going on? George Grizzard is dead. I told him a year ago he should give up smoking. Broadway now more than ever has abandoned itself to high schoolers, mostly female and quasi-female.

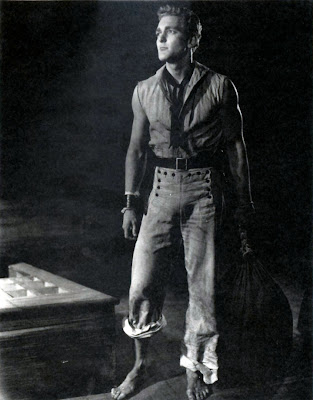

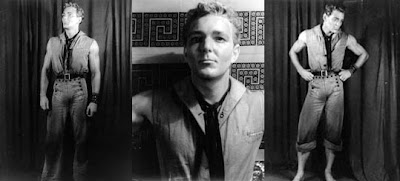

Charles Nolte (as Billy Budd) April 18, 1951.

Charles Nolte (as Billy Budd) April 18, 1951.

I first went to New York at Christmas time in 1942/3 as a kid of 20. In six days I saw Howard Lindsey and Dorothy Stickney in Life With Father, the Lunts in The Pirate, Katherine Cornell, Judith Anderson and Ruth Gordon in The Three Sisters, Tallulah Bankhead, Fredrick March, and a kid named Montgomery Clift in a brand new play Skin of Our Teeth, William Prince in Eve of St. Mark, Ezio Pinza in Boris Godanov at the old Metropolitan Opera . . . Then I went to war. And you ask me what the fuck is going on today?

2) What’s your fondest memory of your 1947 Broadway debut in Tip Top Valley?

Tin Top Valley did not appear on Broadway. It was presented at The American Negro Theatre in a hall on 126th Street, Harlem. I didn’t have an Equity card, and the reason I got the part was because I was just down from Yale where I’d been in the play at the Yale Drama School with a young graduate student named Julie Harris. The play ran for several months. Fredrick O’Neill played a major role. He later became head of Actors’ Equity, or was it The Players’ Club? My memory is hell. I used to traipse uptown several times a week to appear in that play, and I got a nice review from Brooks Atkinson in The New York Times. Of course I was sure I was destined to be the greatest star in the history of the earth. But perhaps my fondest, most endearing memory of that run was the night Butterfly McQueen came to a performance. Everyone remembers her performance in Gone With The Wind. (“I don’t know nothin’ ‘bout birthin’ babies . . .”). She was fun, giggled a lot, despite the dire nature of the play.

3) How different is Broadway today than it was in the 1950s?

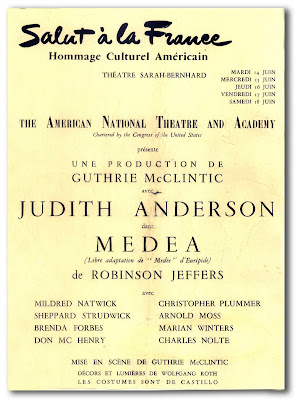

How different is Broadway today? Oh good lord. Is there any comparison (see above)? I remember New Year’s Eve, Broadway, 1942/3, standing in the alley near the stage door, waiting for the stars to come out so I could get their autographs. Of course I was stage struck, and this was The Three Sisters, and there were stars: Katherine Cornell, Judith Anderson, Gertrude Musgrove, Ruth Gordon. Little did I dream THEN that one day I’d make my Equity debut supporting Cornell in Antony and Cleopatra, or that I’d play the Slave in Medea in Paris at the Sarah Bernhardt in support of Judith Anderson! That was what the theatre meant to me, icky school kid that I was.

The Broadway stage today is more or less a playpen for juveniles. Economics have wrecked what used to be a serious enterprise.

4) Through your career first as a theatre student (1942-) turned Broadway performer (1948-), turned drama professor (1966-), what are some of the major changes you’ve noticed in the way the U.S. is educating its theatre artists?

This is too huge a topic for your quiz, at least for me, in this setting. Suffice to say I left the New York stage in the mid-50s, having seen the handwriting on the wall, having by then experienced theatre in major European capitals, etc., etc. I’m glad I decamped for the groves of academe when I did, as I was spared living in New York and trying to make that living in an institution already on life support. I was not on-site to watch and be part of the demise of “theatre as we knew it.”

Major changes in how we educate theatre artists? In 1941 when l first went to the University of Minnesota I took courses in theatre and appeared in a dozen or so productions before I went to war. Back then the only ‘theatre’ was in New York, and if you wanted to be a professional actor that’s where you headed. The professional theatre in America was located between 40th street (the National) and 52nd street (The Alvin).

That was the American Theatre, and in the middle was Shubert Alley where J.J. still kept his office, his two brothers being dead. At the time J.J. and the Shubert Cartel owned almost all the Broadway houses and a great many in London as well. Of course there was no such thing as off-or-off Broadway. And most crucially of all, no such thing as Television! That was all in the future.

So insofar as educating kids to be ‘in theatre’ as performers, your sights were set on that tiny sliver of Manhattan Island. And you played in shows that were old Bway hits, or now and then Chekhov and Shakespeare. Not much imagination, because the New York stage didn’t go in for imagination. Whoever saw a play by Brecht, Pirandello, Maeterlinck, etc., back then on Broadway? Even GBShaw was dicey. And in any case there were precious few departments of Theatre Arts in colleges or universities back then. Yale didn’t have a department of theatre arts for undergrads. Much too suspect, too perverse. They did have a Graduate Department, something Harvard didn’t have, and doesn’t have even today if I’m not wrong. It wasn’t just a matter of aesthetics, but more like a matter of sanitation. I could go on for hours, but you must be tired of all this rant . . . .

5) From your experiences working on stage with Jack Palance, Charleton Heston and Henry Fonda, who was to you the most interesting actor and why?

I love this question. My experience with Jack Palance is nil, except for my days with him on the set for Ten Seconds to Hell, a film made in Berlin in the 50s in which I played an insignificant role. I tried to get Jack and Jeff Chandler who was also in the cast to join me in going over to East Berlin to see the Berliner Ensemble in their old theatre on the Schiffbauerdamm. Living in Berlin much of that year, I had been a constant theatregoer. Brecht had died recently and his widow Helene Weigel ran the company with an iron fist. And acted in his plays as he had directed them: No nonsense. Those productions were revelations, as the world came to realize when the company began to tour. They swept through London like a cyclone. She was the ultimate mother in Mutter Courage, and the primal force in many other Brecht plays. But do you think I could get Palance out of the hotel bar for an evening of theatre? Not bloody likely. Stupid fraud. Martine Carol was also in that film, and even she, French as she was, couldn’t quite bring herself to see a play while in Berlin, even though I considered Berlin the Mecca for Modern Theatre.

What can I say about Heston? Oh dear. We were roommates in two plays en route to Broadway: Antony and Cleopatra, with Katherine Cornell, and Design for a Stained Glass Window, with Martha Scott. I liked Heston, even as a roommate. He had a very large cock. (This was pre-NRA). Miss Cornell called us “the two Chucks.” I think I really liked Heston’s wife Lydia Clark better, and once helped her get an acting job, which she never forgot. I have many stories about Heston over the years. They surface in my journals, which make interesting reading, or so I think. I’ve kept those journals over 50 years now. During the rehearsals and entire run of Caine Mutiny Courtmartial, a period covering three years, I kept the journal daily. It says a whole lot about how a gay man survives in the theatre and in life in the 40s, 50s and 60s, before Stonewall, etc.

Should I publish those sections which are not irreversibly candid, and/or libelous?

The Caine journal material, of course, includes extensive entries dealing with Henry Fonda. I was in the cast of Mr. Roberts for about a year, much of that time while Fonda was still playing Mr. Roberts (before John Forsythe took over the role). And of course I was in Caine with Fonda from the beginning.

I consider Fonda the most interesting actor with whom I worked for many reasons, but maybe I shouldn’t burden you with more of this right now. I did study his acting technique because I was witness to it at first hand, and close up. it struck me as highly professional when it wasn’t frighteningly demonic. This is a love/hate relationship.

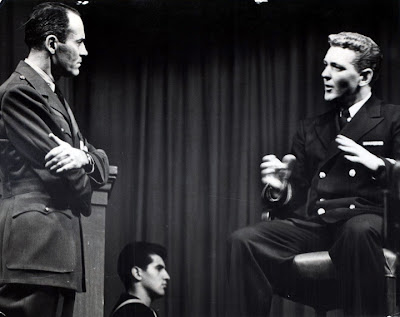

The Caine Mutiny Court Martial (1954).

The Caine Mutiny Court Martial (1954).L-R: Bob Gist, James Garner, Charles Nolte, Henry Fonda, John Hodiak.

6) Do you have any unifying theories that inform your approach to making theatre?

What are my unifying theories that inform my approach to making theatre? Having acted, directed and written for the theatre, I am now more or less in the position of jaded adult audience member, and one obvious and unifying theory presents itself, now more than ever: It is incumbent upon the actor, first to be heard, and second to be understood. The director must help, of course.

I mention this because we have just had the R.S.C. here at the Guthrie Theatre giving us their Seagull and King Lear. Seated in the second row facing directly front, and with excellent hearing in my two ears, I heard about sixty percent of Seagull, and considerably less of King Lear. And to compound the difficulty, I had great trouble understanding much of what I did hear in the Shakespeare as well. What gives?

Sir Ian is OK and almost entirely understandable as Sorin in Seagull, but alas he lacks the fundamental gravitas for a successful King Lear, and falls back on crotchety vocal tricks and mannerisms, and odd inflections and text readings. These would prove more effective in the later stages of the play if at the beginning he hadn’t already spent his wad of ‘old man tricks,’ failing to suggest the regal imperatives his office requires. But what are we to say when the supporting cast is distinctly second-, in some cases third-rate? A lot a dicey acting on that stage. Ought the R.S.C. be sending these boys and gals to do men’s work? So, making Mr. Shakespeare’s language even more difficult to comprehend by their vocal habits and ‘make-work’ acting ill served the play.

I could go on but won’t tire your patience; only to admit to severe disappointment, not in the size and plumpness of Sir Ian’s “member,” as a Roman critic might have called his cock, which was on display for some moments during one of Sir Ian’s many antique tantrums. Of course the audience was distracted. Don’t they call this “stealing focus”? And from some of the more choice lines in the text? And then of course it must occur to the audience as we ruminate on the size of his equipment that Sir Ian would never have made such an artistic choice if his cock had not been reasonably visible from the last row of the theatre.

There were other troubles with these productions. Nina in The Seagull was asked to act very oddly indeed, giving the impression the poor girl was not only a spastic but had disordered emotional problems as well. Oh dear. If Nina is such an oddball, why on earth are the men in that production panting after her? The casting of Nina was so weird that I heard a lot of people wondering if Trevor (Nunn, the director) wasn’t fucking her on the side. She also played Cordelia (not quite as badly). And how does casting Trigorin as just another hippy serve the play? Can you have two hippies more or less the same age on that stage? Constantine AND Trigorin? What damage does that do to Mme. Arkadina’s infatuation with her writer?as a Roman critic might have called his cock, which was on display for some moments during one of Sir Ian’s many antique tantrums. Of course the audience was distracted. Don’t they call this “stealing focus”? And from some of the more choice lines in the text? And then of course it must occur to the audience as we ruminate on the size of his equipment that Sir Ian would never have made such an artistic choice if his cock had not been reasonably visible from the last row of the theatre.

Well, you can see that your question opens a flood gate. Still, the primary consideration is to be heard, AND understood. Only then can you serve the play.

7) How do you feel about the idea that American theatre has – to its detriment – become centralized around New York City?

The American theatre and its centralized location in New York. The question hardly needs posing today. New York has been the center of commercial theatre (and vaudeville, radio, TV, even films at first) ever since the theatre was regarded as a business, which is to say from the very beginning. I don’t know why other cities ceded the distinction to New York, I only know that it has been universal, pernicious, and indefensible.

Actually, the history of our American theatre is the history of a business, the business of theatre. Only recently has this theatre tended toward any kind of rational objectivity, only since the Regional Theatre movement after World War II . . . When I started to think about a ‘career’ in theatre back in the ’40s, there was only one possible destination: New York. Broadway.

There was no theatre in Minneapolis, other than university theatres; Chicago had a couple of touring houses owned by the Shubert Organization which hosted road shows, reproductions of New York successes, produced, directed and cast in New York. New York was the theatre. Tyrone Guthrie in the ’50s had the inspirational idea of creating a not-for-profit theatre midway between New York and Hollywood. The Shuberts were amused.

Don’t call regional theatre a commercial theatre. Theatre in America then meant Broadway; it meant the Shubert houses. 80 to 90 percent of all the theatres in the entire United States were owned and operated by the Shuberts. That cartel was broken by the government, finally, but not until the ’50s, when the government told the Shuberts, “you can own all the theatre real estate, the buildings themselves, but you can’t at the same time dictate what goes into them. Otherwise you’re operating an illegal cartel.” Well, you know all that. And gradually over the past half century the theatre has made steps to disengage itself from commercial considerations and inch back into regarding theatre as a genuine art form, such as we have in the German speaking world, and to some extent in France, and even now in Britain.

Your questions stimulate me into responding with far too long answers.

8) If you could change one thing about theatre in Minnesota, what would it be?

If I could change one thing about theatre in Minneapolis/St, Paul, it would be the establishment of responsible and intelligent criticism. We are chewing on bare gums here. We had a couple of daily papers, one with a fine editorial policy, but neither now with first rate criticism in the arts. Perhaps it is getting marginally better these days. The Star/Tribune eliminated our excellent music critic’s job to avoid health and other benefits, despite the fact we have two world-class orchestras here, an excellent opera company, and numerous other musical groups, etc. etc.

They retained the job of our major theatre critic, who is not well qualified for his position, in my opinion. Most other criticism is freelance, some good, some not. The University of Minnesota at one time filled a critical need by eductating huge classes of students every year in theatre, several thousand per year, encouraging many of them into actually attending the theatre. They form the backbone of our current theatre/music audience. But we need really astute critics.

9) What do you know about theatre now that you wish you knew when you were younger?

Everything and nothing. Youth will be served, and I would have gone into the theatre one way or another, and probably remained in it despite bruised ego, absence of security, and all the other traumas associated with our gypsy life.

Thank god I had a leg-up in academia, a position which provided the essential props for security, pensions and health benefits, etc. Academia gave me something else in the way of perspective: the fact that I spent my university teaching career mostly lecturing to large groups of students, I was able to indulge latent acting skills on a daily basis. Keep ’em amused. Attempt to generate excitement, stimulate their minds. I found rather quickly that theatre history involves not only the history of the theatre itself, with all that implies, literature, plays, productions, but also sidebars in archeology, anthropology, psychology, psychiatry, sociology, medicine, music, dance . . in fact, everything. Theatre is the one great public endeavor, it embraces everything.

What could be more exhilarating than facing 500 kids every morning and telling them about Oedipus and his mother? Or the troubles Medea had when her husband wanted a divorce?

10) When you look at the varied landscape of contemporary American theatre, what are you most optimistic about?

I can be optimistic about the theatre, the fact that it is accepted in schools, actually taught, not fought against, as it used to be. When we at the University of Minnesota finally badgered our state legislature into funding our new building, after 35 years of begging, after surviving for half a century in an old barn, we still found it necessary to remove the word “theatre” from our proposal at the legislature and substitute the phrase “Performing Arts.”

That word “Theatre” was still considered too incendiary by the dons of government. It goes without saying that you could get more money for the eradication of croup in chickens than you could for anything called a “theatre. “ Times have changed, Deo Gratia.

I am optimistic about the number and, now and then, the quality of theatre, especially here in the Twin Cities, where we have quite a vibrant theatre scene. Other cities and states are not so lucky. The Detroit area, where I am about to go to direct in the only L.O.R.T. theatre in the state, is abysmal. And New York, our vaunted seed-bed, is now a play-pen for kids of all ages.

Economics is still the major crippling factor. Broadway, Manhattan, that’s pricey real estate. We need all these regional theatres to get in the habit of nurturing their own new young playwrights, not depending on what leaks out of New York. All in all, I can be optimistic about the theatre and theatre people, but find myself less so about politics and life in general.

What do you think? Has the human race another 20 years?

I did my undergrad work at University of Minnesota and had a class on Modern Drama with Dr. Nolte. At the time, I remember that most of my friends adored him, but I was annoyed because I didn’t agree with his take on modern drama. Now, I find myself in total agreement with what he said. I just wasn’t capable of hearing his ideas at that time — but I remembered them. I also remember a moment in an audition that I blush to think of. I had just done my first leading role at U of MN — Shawn Keogh in Playboy of the Western World, and I had been a “hit,” and I followed it up with a performance as Simon Stimson in Our Town, which had also been well-reviewed. The next semester, he was directing Horvath’s Tales from the Vienna Wood. I had just fallen in love with the woman who would be my future first-wife (*LOL*) and so I was really full of it. I wasn’t nuts about Horvath’s play, so I wrote on my audition sheet: Leads only. I remember having done my cold reading, and then hearing Dr. Nolte’s velvet voice from out of the dark auditorium: “Ahem, Mr. Walters? Does this say “leads only”?” “yes, it does,” I replied. There was a silence, and then “Thank you very much.” And that was the end of my audition. I also remember that he had wonderful cast parties at his house, which he ended by playing a particular piece of music as a cue that we all should go home. I don’t remember what it was, but it strikes me it was Wagner. It was interesting to read this interview and find myself so much in agreement with just about everything he had to say. Greetings, Dr Nolte. I hope you are well.

Wow, Dr. Nolte, thanks for sharing your thoughts with a website run by a bunch of relative neophytes. I think I may read this over a few more times, just to ingest it all properly…One clarification, Harvard does have a graduate program – I graduated from it. It was established by Bob Brustein after he left Yale. They started giving out MFAs when they combined with The Moscow Art Theatre School in 99. Again, thanks for taking the time to go into such candid detail.

Dr. Nolte,

What a pleasure it is to read here your thoughts on theatre – its past, present and possible future. And what an abundance of funny and piercing insight you have at your disposal.

Among the long list of moments in this piece that floor me, is your description of Henry Fonda’s acting style: “highly professional when it wasn’t frighteningly demonic.”

Wow.

May I submit, for your consideration, answers to some of the questions you have asked here?

“Should I publish those sections which are not irreversibly candid, and/or libelous?”

Yes. Please. And the libelous ones too, if you can.

“What do you think? Has the human race another 20 years?”

God I hope so. Is personal action, informed by an abundance of hope, enough to halt the decline of the human empire? Or has absolute power corrupted so absolutely that the decline is irreversible? I don’t know. Let’s ask our cats. They seem to know what’s going on.

Again, thanks so much for this Charles.

Ian

Wow. Just…wow. Must…type…through…speechlessness.

Deep breath. Okay.

First off, congratulations on a truly magnificent conversation. What a coup, and yet another clinic in the true art of interviewing. Dr. Nolte, thank you so much for sharing your candid opinions and experience with us newbies, your veraciousness is both generous and highly entertaining. It’s clear how you found a home in academia, I’m sure your students are the better for it.

Those who don’t learn from the past are doomed to repeat it…I wonder how much further along we’d be if we took the time to discuss theatre with its elders, especially those who were around when people would wait outside of theatres in hopes of scoring an autograph from a stage actor. Past theatre lives in the memories of those that experienced it, storytellers all, I for one would love to hear more of their stories…

That was awesome.

A friend found this interview after hearing Dr Nolte had passed on. January 14, 2010. How wonderful to hear his thoughts again. Stunning.

I have been blessed to design for Charles as Director (including some World Premieres of his) on nearly two dozen professional productions. He was always a joy to work with.

Plus, he was a joy simply to know. What a kind heart. He deeply touched so many. He will be missed.

In 1956, Phipps played the part of Booth’s cowardly drunken co-conspirator, George Atzerodt, on the live Tver, “the Day Lincoln was Shot.” Booth was played by Jack Lemmon. They had a great moment together. Phipps was very good in the role. I wish I could find some comments or recollections of his work on that show, as I am writing an article on the making of the program. The great Delbert Mann directed it.

There is apparently a typo in the answer to question 6. A portion of paragraph 4 has been “pasted” onto paragraph 5, at least in my browser.