1) What the fuck is going on?

1) What the fuck is going on?

We don’t talk on the phone any more. We silently communicate by email. Is this good? In a way. The phone is a most peculiar instrument; I mean I could be talking to someone who’s making faces at me and I’d never see it.

Emailing can feel like letter writing, which is good. Except that it is so fast, I wonder if the poetry and ruminations of the old writing-by-hand method is being lost. One thing we must never do on email is to get angry. I have learned that angry or passive-aggressive email can do terrible damage. People keep nasty emails, so they can use them for later. Long after the war is over . . .

2) What have been some of your biggest creative challenges since becoming Artistic Director of Nightwood Theatre?

Creative challenges of Nightwood . . . you know, there are so many creative people on standby to be invited to do their shows, or act, or design, that the only real problem is to find the money space and time to let the artists “go at it”.

3) Are there any overarching themes or ideas that are common to the work being presented in Nightwood’s current season?

The theme for this season is, “Women who refuse to behave. A risky business.” Right now, a nanking winter by Marjorie Chan is on at The Factory Theatre. It’s about a writer who exposed a terrible historical event, and then has to face attack for daring to do it.

4) During your time as Artistic Director for Toronto’s Young People’s Theatre, did you arrive at any conclusions about theatre and its relationship to at-risk communities?

Yes. So much TYA is trying to show kids the way the world should be. They paint a politically correct perfect picture. But I think kids at risk, in areas such as poverty, or bullying, or abuse, can see through that crap. I think two kinds of theatre work for communities at risk:

One is to do good theatre that acknowledges their truths, and helps them to discover courage in themselves, and maybe that theatre should come right into their community.

The other way is to make theatre available that gives them a fabulous time, sitting in a big house, with all the bells and whistles, and great acting/singing/dancing/writing . . . a good story that transports them, without patronizing them . . . you know, ENTERTAINMENT!

5) How important is it for theatre makers to be actively challenging systems of oppression in their work?

We shouldn’t be doing theatre unless we have a passion and understanding of how things work in the world, in our world, how others are handling life. Otherwise it is a wank. We should try to influence the thinking of those we do theatre for. It is by acknowledgment of the way things are for people that we can create exciting theatre that promotes the challenge of authority and the bravery we need to demand a better world, justice, truth.

6) Is children’s theatre an effective “gateway drug” for turning kids into long-term theatre patrons?

6) Is children’s theatre an effective “gateway drug” for turning kids into long-term theatre patrons?

No. So long as we herd hundreds of children into a theatre, they will behave like a herd, and not like individual theatre patrons. If we come to their school, they will treat us like part of their education.

7) What qualities do you look for when committing to the development of an emerging artist?

An awareness of the world, and a fabulous imagination. A way with words.

8) Do you have any unifying theories about the role of formal education in shaping theatre artists?

It’s great to hang out with other emerging theatre artists. But unfortunately too many professional theatre training programmes are training kids of privilege, because they are the only ones who can afford to dream. Humber College, however, is one program that tries to bring a diversity of students in areas of race and privilege.

9) How do you feel about the fact that so many members of your family are active in the theatre community?

They are hugely gifted people, so I am proud. I used to worry when they were unemployed, but they are so seldom out of work, I now only have to worry about myself.

10) How much of your approach to storytelling is informed by your experience with Icelandic narrative traditions?

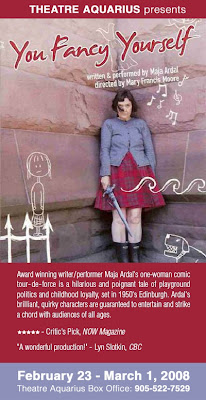

My mother told me stories of our family as I was growing up. She kept the whole world of our ancestors and relatives alive in my imagination, and her stories were and are fantastic. Storytelling is what Icelanders did during the long dark winters. And there are more poets and published writers per capita than anywhere else in the world, I understand. It is no wonder that two of my plays are so inspired by storytelling tradition, especially You Fancy Yourself, in which I perform 12 characters on a journey that crosses the cultures of Iceland and Scotland.