1) What the fuck is going on?

We are witnessing the Schiavo-ization of theat – wait, wrong cue-card . . .

Sorry, I’m goofing off because the question freaks me out. I don’t know what the fuck is going on. I want there to be one spot I can look at and see the whole thing, but there is no such spot. This was something I loved about the recent film Cloverfield, that the glimpses of the monster were metaphorically true to what I experience when I try to look at the world around me, or even at myself: there’s a leg – oh – wait – there’s the jaws for a second – there’s the eyes – wait, there it’s going around the corner and I barely saw anything! I can’t see what’s happening while it’s happening. There’s too much work, too much need for entertainment and sensation, too many places to be.

I’d actually be relieved if folks in comments didn’t share this feeling with me. It would make me feel like I could see a shrink or go on meds and make it go away. What I’m afraid of is that this feeling may be shared.

On the upside, I live happily with my partner in Brooklyn, last year was the best artistic year of my life, and there’s fun projects and hopes on the horizon. I have great friends, great colleagues, a great family. I live in an amazing place, a converted auto-body shop. It’s huge. (It won’t last. East Williamsburg or whatever you call it is just about to go through the roof and then we’re all out on our asses.)

2) What’s the best thing about being a playwright and actor in New York City?

Well, I love New York City. I loved New York before I loved theater. My father brought me here on a trip when I was 9, before I gave a crap about plays, and I fell in love with it. I always knew I would live here. Perhaps I’ll change my mind about that some day.

To answer your question: there’s always something to do and some place to do it! Sure, about once a year I have to put up my own dough to produce something, but people are also putting on one-act festivals all the time, and they’re always looking for writers. Once you get a basic foothold and people like your stuff okay, you can get involved in a lot of projects and get produced a lot of places. Tiny places, I won’t lie, but you can have fun in a tiny place.

New York’s particularly fun for an amateur actor like myself. If I happen to be free and feel like acting in something, there’s usually icro–budget plays by interesting playwrights looking for actors. I’m a funny–looking dude with bad posture, but Off–Off Broadway, they can use me! I get to be in plays by cool playwrights like James Comtois, Dan Trujillo, Van Badham, Ed Malin, etc, in neat roles professional actors would have to turn down to leave themselves free for something that paid a living wage.

It’s quite a different experience to be a professional actor in New York. You have to go on an endless mill of auditions, some of which are humiliating. You have to be a reader. You have to constantly beg your boss for more time off in the afternoons, or you have to work at a restaurant. You have to take countless jobs out of town (where you will be exacerbating other problems, but that’s another story), sublet your apartment all the time, spend thousands flying back for auditions, never feel like you have a home, compare yourself to others – fuck that, dude, seriously. Nearly everyone I know who came to New York to be an actor has shifted their energies to some other aspect of theater, and treats acting like I do, as a supremely pleasurable hobby.

3) As a writer, do you make any clear distinctions between “structure” and “language”?

I do. Language always came easily to me. As long as I’ve been an adult writer, I’ve been able to do pithy lines of dialogue, and, a bit later, could even write beautiful and poetic language if I put the pedal to the metal. But I always had a hard time constructing my plays around a disciplined structure.

Now, structure doesn’t always mean “plot,” though for me it does. For some playwrights, they structure their plays around the completion of a complex physical movement, or a piece of poetry, or a dawning realization, or a completely articulated thesis. Or something else. The point is that the dramatic event is moving from one place to another, and every moment is a segment of that movement if the play is structured properly. If not, many of those moments sort of lounge around indulgently. No matter how sophisticated or subtle you think your play is, at some level the audience can sense the innate basic movement of the piece, and can sense just as keenly when you’ve gone off the rails. They start shifting in their seats. They start getting hungry and tired.

For a number of years I wrote bloated plays, with a lot of indulgent moments in them, moments I put in and left in because an idea happened to pop in my head and I hadn’t yet learned that every idea you have while writing a play doesn’t necessarily need to go into THAT PARTICULAR PLAY. You can save some for later. Writing short plays – five minute, ten minute, fifteen – forced me to learn structure. Every beat had to count. I was delighted to find that I could bring that newly acquired skill back to full–lengths. When we did Universal Robots last year, it was almost three hours long, but almost nobody in the audience got bored (with a couple exceptions – I was watching closely). The play happened to be structured well enough that the audience could sense that I wasn’t wasting their time. Most of the moments were necessary to make the next moment happen. We’re remounting it next year, Spartans, so the goal is to get 100% essential moments!

I read a review of that post-9/11 play The Guys in the New York Press that defended the play’s bland language by saying something like “great language has only ever had an incidental relationship to great drama.” I can see that upsetting folks, but I can’t deny that it’s true for me. It’s hard for me to just listen to beauty. Elegant language, potent language, poetic language – I can’t sit still. I like rising tension, conflicting agendas that can’t possibly be resolved to the satisfaction of both parties, romance, sex, unrequited love, plot twists, hearts breaking in real time.

But embedded in your question is the suggestion that the two can’t be extricated from one another, and I’d ultimately have to agree with that. When I’m putting a play together, I know I have to work out the language in tandem with the structure. Plays can only be broken down into component parts in discussion, not in creation.

4) How have your experiences with theatre blogging influenced your ideas about theatre?

Actually, not much. Partly that’s because I don’t have many ideas about the subjects of controversy that have defined the theatrosphere because I’ve never had any funding, I’ve never had a regional production, I’ve never been in development or had a dramaturg, I’ve never intersected with the professional side of the business to know in my bones how crucial the “new models” discussion is. I was most engaged a couple years ago through the whole debate about the power struggle between directors and playwrights, because that spoke to my experience, in the rehearsal room, making plays. Since then, the conversation has tended to move away from what I know.

Also, the conversation’s gotten angrier and more abrasive. I’m not absolving myself; I’ve contributed to that. Even recently. And I’m ashamed of it. But what I’ve found is that I may be too thin-skinned to be a blogger. The theatrosphere has become, inevitably, like any other blogosphere. There’s no point in me griping that it’s not a cozy little club anymore. It shouldn’t be. But one result is that folks are meaner, and the ones willing to go the most on the offensive will be predominant in the end.

When I get involved in a flame war, I’m traumatized and unhappy for a few days after. And it makes me more afraid to blog again. (Hell, I can hear someone in my head telling me to quit whining as I type this.) And it recently occurred to me that post-flame war trauma can’t possibly affect people like Scott Walters or Don Hall or Leonard Jacobs or Nick Fracaro, ’cause they get right up and keep blogging the next day. They’re the roaches who will survive the nuclear war – tough. I’m not. And I don’t know if I will continue. I don’t enjoy it much anymore, and that’s reflected in my posting. Increasingly, I feel like the only way for me to go on might be to stop trying to participate in existing conversations and start a few of my own. I don’t know.

5) Why is your blog called “SlowLearner”?

Truth in labeling. I learn very slowly. I have to put myself through the same shit over and over again before the lesson finally gets through my head and I adjust. It makes my girlfriend crazy. (It’s an interesting experience, cohabiting – in a way, you see yourself for the first time.) I have to learn the lesson repeatedly before I change. And I have no career savvy whatsoever. Learning to do the basic things other playwrights have been doing for years to secure work and notice has just barely begun for me, recently.

6) How important is it for artists to be actively challenging systems of oppression with their work?

Um . . . well I guess I don’t know the degree to which an artist can challenge a concrete system of oppression. I can’t write a nifty play – nor indeed can Tom Stoppard – and in any way challenge Kim Jong Il. What we can do, perhaps, is analyze the way we conduct ourselves as moral beings within the systems we find ourselves. Many systems have been overthrown to be replaced by something worse. The key is to find courage, and clarity, and an honorable way of living, and I can feel myself trying to find that through writing plays. So far I’ve figured out that I’m quite a ways away from all three.

I wrote about this a lot here.

7) How do you feel about the idea that American theatre has – to its detriment – become centralized around New York City?

Well, it’s great for me! You know those exploiters that you hear about who take advantage of the zillions of artists crammed together in New York who are desperate for any chance to do anything? I’m one of them! I get to work with incredible people for next to no compensation!

In all seriousness, wonderful artists (starting with my coproducers Sean and Jordana Williams) have made great sacrifices of their time and energy to work on my plays. I would really, really like to pay these people properly some day. I love the Equity Showcase, and the opportunities it affords me, but there’s always a nasty feeling that I can’t do more to remunerate people. I don’t regard money as a hollow, superficial force; money is a means by which you honor other people’s time.

Weirdly, when I’m the one working on a play I like for free, I don’t mind or feel exploited at all. So that’s a contradiction. I can’t deny it.

8) When you look at the varied landscape of American theate, what kinds of stories do contemporary artists seem to consistently neglect telling?

There are way too many plays out there, and way too many productions, for me to speak in general terms. In terms of my anecdotal experience, there are two kinds of plays I’d like to see more of:

1. Plays that work with genre – science fiction, fantasy, horror, mystery. Our culture is obsessed with these forms, and I think our most powerful statements are often transmitted metaphorically through the fantastical. I think theater can express these forms in unique ways, and that’s been emerging as the only thing I could call my mission as a playwright. I know James Comtois and Qui Nguyen are two others also interested in this. I think Tracy Letts’ BUG was inspirational to a lot of us in this respect. I remember sitting bolt upright watching that exhilarated: “Oh my god – I guess I’m NOT supposed to be slightly bored at plays!”

2. Plays that build. One of the thrilling things about the last three seasons of The Wire have been the ways the show has followed unconventional thinkers stuck in broken systems surreptitiously attempting innovative solutions. I part with the consensus in finding the show to be incredibly optimistic. It seems to suggest that what we need more than anything else is room for some trial and error.

I agree with Hunka that some plays should lead us into an unfiltered reckoning with what is darkest in ourselves. SOME plays. I think that’s a worthy purpose (and George, God knows I’m being reductive here). But I’d like to see more plays trying to build something new, seeking for ways to function within the chaos and corruption of our circumstances. They don’t have to be Pollyanna–ish, they just need to strive a bit.

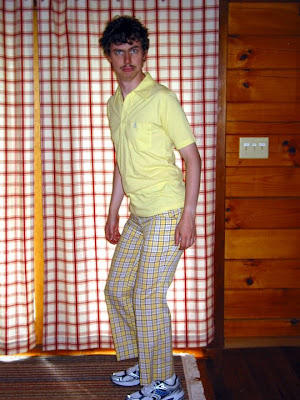

Mac Rogers as The Nervous Boy from The Adventures of Nervous Boy

Mac Rogers as The Nervous Boy from The Adventures of Nervous Boyby James Comtois for Nosedive Productions. Photography by Aaron Epstein.

9) How much of your work is informed by a sense of anger?

Almost none of it. My work is informed by terror. I start from a place of weakness and fear, and try to see where it leads. I have the liberal’s weakness, of seeing an injustice in society and instead of doggedly and dogmatically trying to fix it, at any cost to anything else, I go to self analysis mode, wondering what I and others who resemble me may have done to allow this injustice to exist, and what weakness in ourselves may have led us to do that thing. I learned this reaction from reading the works of Wallace Shawn in my mid–twenties, which was incredibly influential on me.

The one thing I ever wrote from anger was this big goofy musical I cowrote with Sean and Jordy called Fleet Week, which was sort of a gay On The Town, but written in reaction to learning about the number of voters who cited a dislike of gay marriage as a key reason to re-elect George Bush. The show is mostly smutty comedy, but it’s angry smutty comedy.

10) As a writer, what are you better at now than you were when you were younger?

The most important thing I ever learned as a playwright was that the play I was currently writing wouldn’t be the last one. Halfway through writing a play, you get tired of it, and you get an exciting new idea, and something happens in society that makes your current project feel not-of-the-moment in some way. Recognizing that you will write another play later allows you to push through that stuff and allow each play be what it needs to be. The second-most-important thing I ever learned was to write the sort of plays I’d have a blast watching. They’ll still be personal and relevant – that stuff just sort of seeps through. Making them exhilarating – that’s where the effort is.

I’m worse at some things. I don’t give my characters the same breathing space I used to. I used to be more generous with them. I used to let them have unessential moments where I learned charming little things about them. That’s jettisoned now, for the time being. It’s a tradeoff.

Mac, when did you move away from Astoria?!

You LEFT us.

That’s it, gloves are OFF.

I’m telling folks that you used to work in a bank and wore a suit and tie.

There. Consider yourself OUTED. Heh-heh.

Mac, with all the nice things you have been saying about me here and there in the comment sections of other blogs, I have to assume that your reference to me here as a cockroach is a compliment. However, I am as human as you are and often as traumatized as you claim you are by the theatrosphere wars. I don’t always “get right up and keep blogging the next day.” (Ian himself has scolded me for not posting enough.) My blogging is a very difficult job for me. But the debates that I enter (sometimes initiate) I believe are necessary and important vehicles for examining our relationships to our peers and the art form of theatre.

Josh, what can I say – I did for a broad! However, you will note that my sartorial standards have improved astronomically.

Nick, upon glancing at your archives, I see that they bear out your correction here. I apologize for mischaracterizing you.

I love this:

“My work is informed by terror. I start from a place of weakness and fear, and try to see where it leads. I have the liberal’s weakness, of seeing an injustice in society and instead of doggedly and dogmatically trying to fix it, at any cost to anything else, I go to self analysis mode, wondering what I and others who resemble me may have done to allow this injustice to exist, and what weakness in ourselves may have led us to do that thing.”