Mac Rogers

Mac RogersPhoto by Saundra Yaklin.

We are witnessing the Schiavo-ization of theat – wait, wrong cue-card . . .

Sorry, I’m goofing off because the question freaks me out. I don’t know what the fuck is going on. I want there to be one spot I can look at and see the whole thing, but there is no such spot. This was something I loved about the recent film Cloverfield, that the glimpses of the monster were metaphorically true to what I experience when I try to look at the world around me, or even at myself: there’s a leg – oh – wait – there’s the jaws for a second – there’s the eyes – wait, there it’s going around the corner and I barely saw anything! I can’t see what’s happening while it’s happening. There’s too much work, too much need for entertainment and sensation, too many places to be.

I’d actually be relieved if folks in comments didn’t share this feeling with me. It would make me feel like I could see a shrink or go on meds and make it go away. What I’m afraid of is that this feeling may be shared.

On the upside, I live happily with my partner in Brooklyn, last year was the best artistic year of my life, and there’s fun projects and hopes on the horizon. I have great friends, great colleagues, a great family. I live in an amazing place, a converted auto-body shop. It’s huge. (It won’t last. East Williamsburg or whatever you call it is just about to go through the roof and then we’re all out on our asses.)

2) How do you feel about the idea that Canadian theatre panders to a “cultural elite”?

Panders to a “cultural elite” as in “intellectual elite”? I hope theatre does that. I tend to like the theatre that assumes as a premise an intelligent audience. I think we often pander to the Euro-centric financial elite, is that the question?

There’s a historical relationship between the affluent classes and the artist and that hasn’t changed. And theatre, as it arrived in Canada, is a European art form. It’s hard to shake that off.

3) What is your fondest memory of being on stage?

My favourite memory of being onstage would have to be bombing at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre in New York City during the Del Close Marathon in 2003. The marathon itself is the ‘big show’ of improv and I was there with my troupe, Tonto’s Nephews.

Leading up to the festival we had been getting some interest from CBC and the Winnipeg Comedy Festival, as well as some other television development stuff. The fact that we were an all-Aboriginal Comedy Troupe was appealing apparently and there had been talk that some NBC Diversity people were going to be watching us at the festival to see what the hype was about.

To make a very long, boring story short, we went and we sucked. We had an amazing time slot, the theatre was full,

half of the cast of

Saturday Night Live.”

and in the first row of the audience sat half of the cast of Saturday Night Live. We went out there and made ourselves look like fools. No one was listening onstage, two of our ‘stars’ bullied and trudged their way through their storylines, and the whole show crumbled – it was 30 minutes of shitty improv. I don’t even remember if we got any laughs.

When I got off the stage, I went straight to the back of the room, and by chance I ran into Horatio Sanz. He knew I was steaming mad about being bullied off stage during the improv set and he pulled me aside and for about an hour he told my what he liked about my style, we talked improv and where it’s going, and we teased a bunch of drunk UCB ‘chicks’, or, ‘groupies’, and it was an incredible time.

Sucking that badly onstage at such a huge comedy festival was a humbling performance moment for me. Everything I had worked for to get to that day exploded in my face. After I left the theatre I went for a walk to Central Park, sat under a tree, and started to think about what would become MooseGuts Theatre.

4) How do you feel about the idea that American theatre has – to its detriment – become centralized around New York City?

It’s always been centralized around NYC – that has never really been to our detriment. NYC is a great town with great artists. The focus on bigger and bigger houses, more and more money, has done the damage and NYC is also the capital of “Selling your Mother for the Highest Price” as well.

Broadway is a bloated, celebrity-driven whore overtaken by Disney and Sony. Somewhere along the line, the money-lenders realized that if you dressed up a high-concept turd with enough flash and dazzle, enough stage gimmickry and had a Hollywood star perform in it, they could make the fast turnaround buck. NYC has given birth to so many good things for American Theater but the good things are now being over-shadowed by the money-grubbing greed factories looking to shill the tourists. When the accountants become the producers and the artists, in a drive to create “mass art,” write plays that are increasingly less complex but highly entertaining, the art as a whole suffers.

The truly unfortunate thing is that it works and everybody wants to get some of that golden pie. So you get Cirque du Soliel in Vegas and Broadway in Chicago and the Guthrie “Megaplex.” The big glitzy horseshit that passes as theater in these monstrously large organizations obliterates the new and the original. When originality is stomped on and buried, the outlook gets pretty grim for all but the hacks responsible for “destination shows.”

It is easy, however, to throw blame at the snake-oil salesman of Broadway and thus paint all of New York with that broad brush. New York has a rich history of great theater and deservedly so. There are also scores of New York artists that are not a part of that system, churning out countless plays and musicals that don’t buy into the corporate model of Deadly Theater. Most importantly, New York has a culture of theatergoers – it is a part of the population’s regular list of “Things to Do” and that can’t be said of most places west of the Apple.

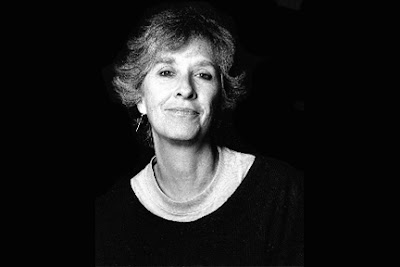

5) What does it mean to you to become a member of the Order of Canada for “contributions to the success of Toronto’s Tarragon Theatre, and for helping to foster a vibrant national theatre scene”?

Becoming a member of the Order of Canada happens to other people; it never occurred to me that it would happen to me. The fact that I knew some of the people who were members was enough. I pinch myself and, of course, like everyone else (of a certain age) who has received an honour, I wish my parents were around to witness it. “See, dad, even in the arts, you can be acknowledged.”

Working at Tarragon has been almost a total joy. I consider myself to be extremely fortunate to have worked so long at a theatre that has maintained its fundamental focus even as it grew and adapted to the changes going on around it. Luck has a lot to do with it and maybe an ability to see a good thing when it’s placed in your path. When I started at Tarragon – in 1972 – professional theatre as we know it today was still a work-in-progress. Just by being a part of it, you were “helping to foster a vibrant national theatre scene.”

6) When you look at the landscape of contemporary Australian theatre, how much of it seems to be built on (or make explicit reference to) the country’s Aboriginal performance traditions?

Not much. There are some excellent Indigenous theatre companies and artists: Stephen Page’s Bangarra Dance Theatre is probably the best known internationally, and there is a strong contemporary tradition of Indigenous theatre, with shining talents like the director and playwright Wesley Enoch. But it doesn’t integrate with the mainstream theatre conventions as much as you might expect.

Why that is so is extremely vexed. Some of it is about the understandable sensitivity Indigenous people feel about cultural appropriation, and the reluctance of white artists to step on those sensitivities. To say this is a complex area is somewhat understating it…!

7) How do you feel about a theatre critic’s power to make or break a show?

A critic should not have the power to make or break a show, but unfortunately audiences are extremely cheap and lazy and are all too happy to give them that power. I have been really dissatisfied with how theatre criticism works in this city for quite some time now – the ego surrounding it is so, so huge, and no wonder. In a job like that, where you’re paid to be judgmental, it’s easy to turn into an asshole and develop an inflated sense of your own importance. The challenge is to maintain your modesty and realize that the most important part of your job is to create a tangible record of an ephemeral experience and, maybe, introduce your readers to something new and wonderful that they might otherwise have dismissed. Anton Ego, the ominous food critic in Ratatouille, has a monologue at the end of the film that sums up exactly how I feel about criticism:

“In many ways, the work of a critic is easy. We risk very little yet enjoy a position over those who offer up their work and their selves to our judgment. We thrive on negative criticism, which is fun to write and to read. But the bitter truth we critics must face is that in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is more meaningful than our criticism designating it so. But there are times when a critic truly risks something, and that is in the discovery and defense of the new. The world is often unkind to new talent, new creations, the new needs friends.”

8) What advantages does poetry have over other modes of narration?

Levels, layers . . . I love levels. I want my work to exist on many levels. I want the audience to have a rich and complex meal. Story is lovely – but for me – I need the mystical, the organic movement of a tree in the wind – so that the audience can’t go, “Oh, I get it, that’s how it ends. It is about a man who . . . ” I want them to question, get a little lost . . . I want to move closer and closer to something that is NOT just words – but is something that can really only exist on stage, live . . . But is not just movement design or raw emotion. I want it to have an elegant container that grows organically from the content.

9) What is pub theatre?

Really, simply put, theatre in a pub. In the UK and Ireland, pub theatres tend to have one resident company (usually indie). The theatre space is a well-appointed black-box often on the second floor of the pub. Productions frequently transfer out to other venues after initial runs. Many of Conor McPherson’s plays debuted in pubs.

Historically, The Public House has acted as the centre of the community. This was a meeting place for the people. With its gritty, sawdust coated floors, The Public House gathered local voices in a shared space.

Ideas and performances are exchanged in this dynamic intersection of theatre and community.

10) During your time as Artistic Director for Toronto’s Young People’s Theatre, did you arrive at any conclusions about theatre and its relationship to at-risk communities?

Yes. So much TYA is trying to show kids the way the world should be. They paint a politically correct perfect picture. But I think kids at risk, in areas such as poverty, or bullying, or abuse, can see through that crap. I think two kinds of theatre work for communities at risk:

One is to do good theatre that acknowledges their truths, and helps them to discover courage in themselves, and maybe that theatre should come right into their community.

The other way is to make theatre available that gives them a fabulous time, sitting in a big house, with all the bells and whistles, and great acting/singing/dancing/writing . . . a good story that transports them, without patronizing them . . . you know, ENTERTAINMENT!